90 DEGREES EQUATORIAL PROJECT

McClelland Sculpture Park+Gallery 2017-18

Resurveying Site, Zhulong Gallery, Dallas Texas 2015

Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide 2007 (Now ACE)

GAGPROJECTS

Conceptual landart project

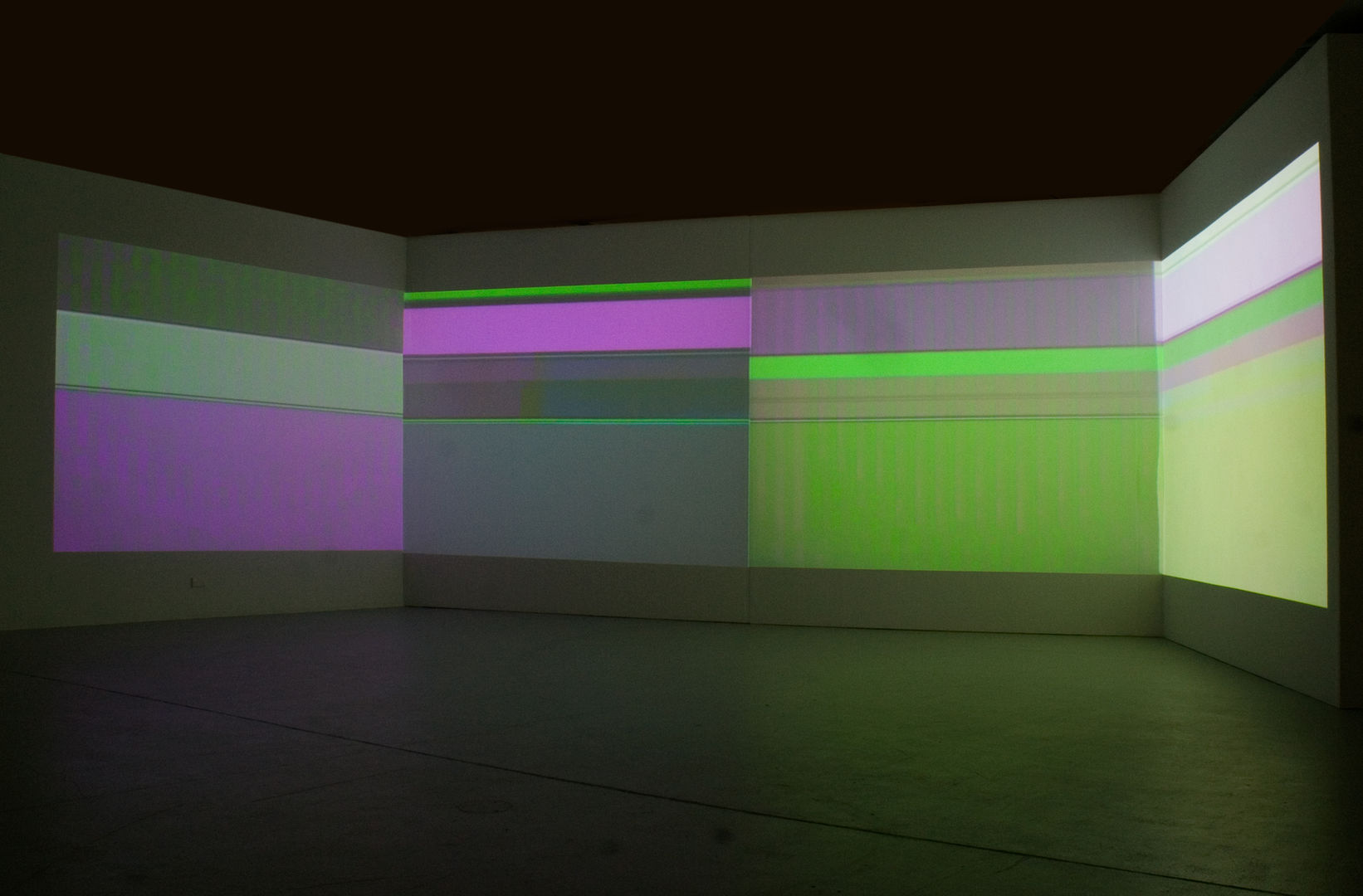

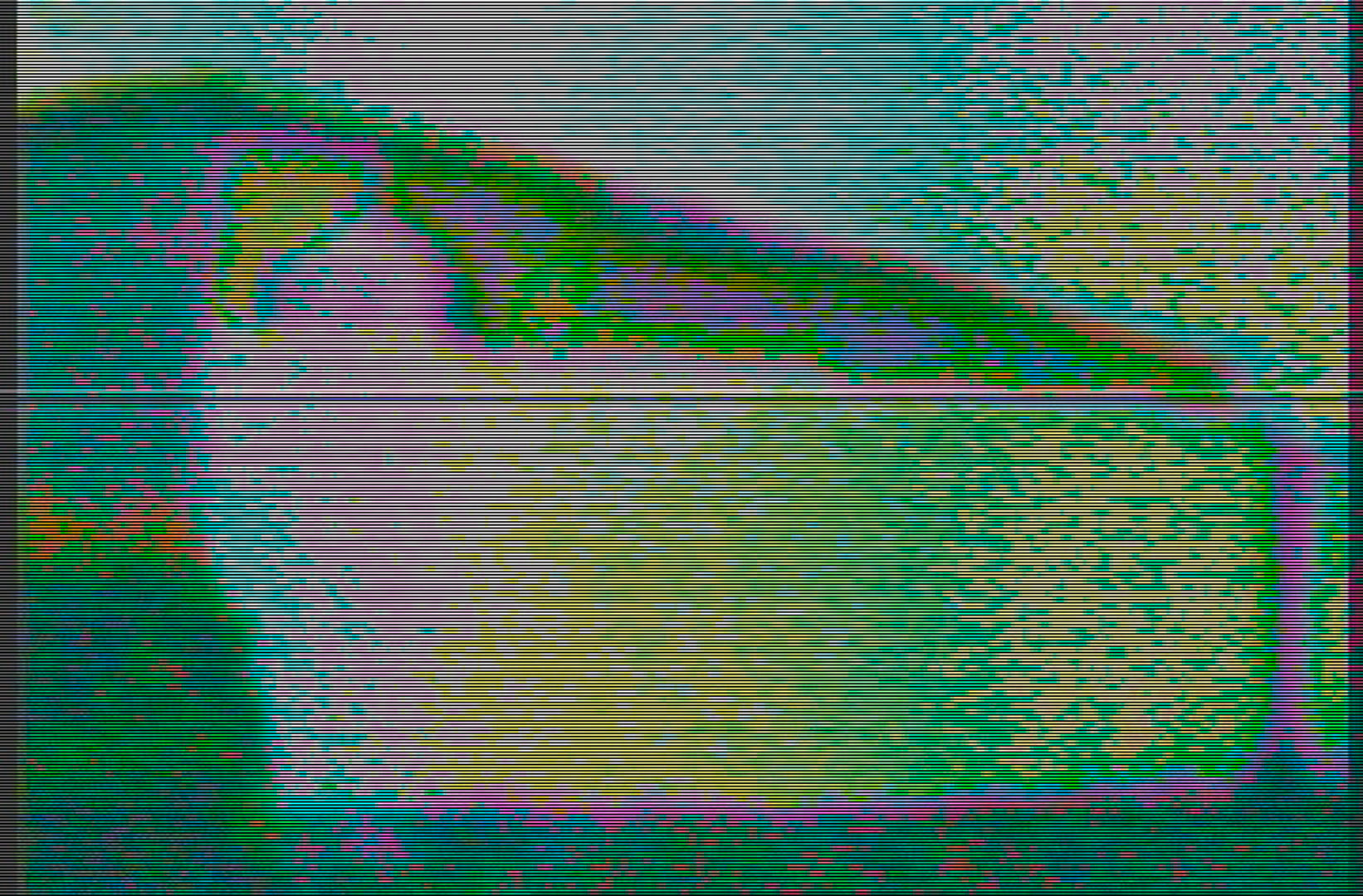

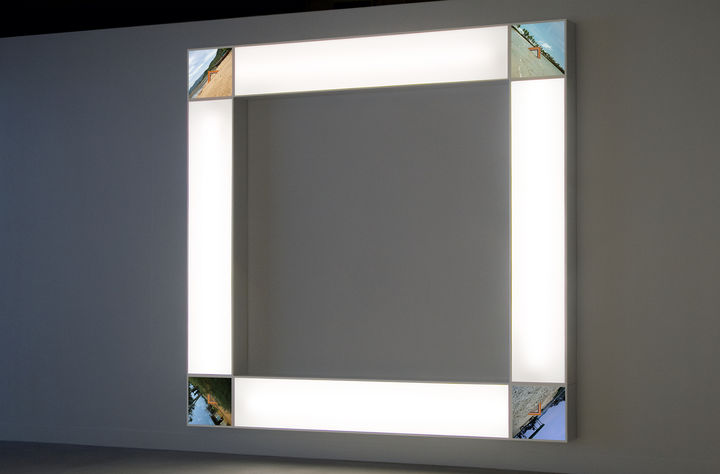

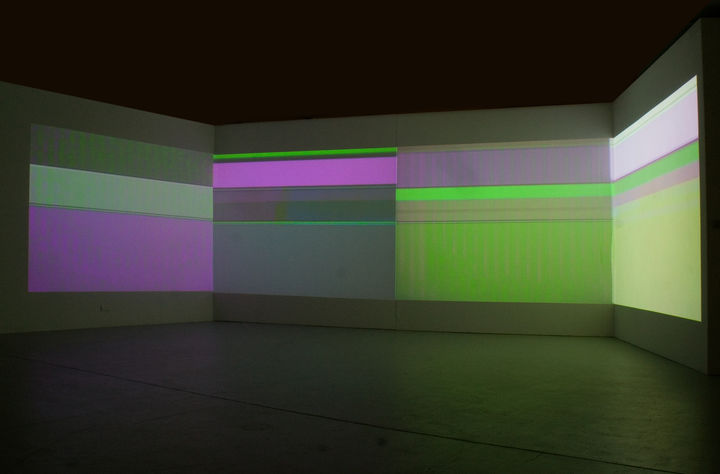

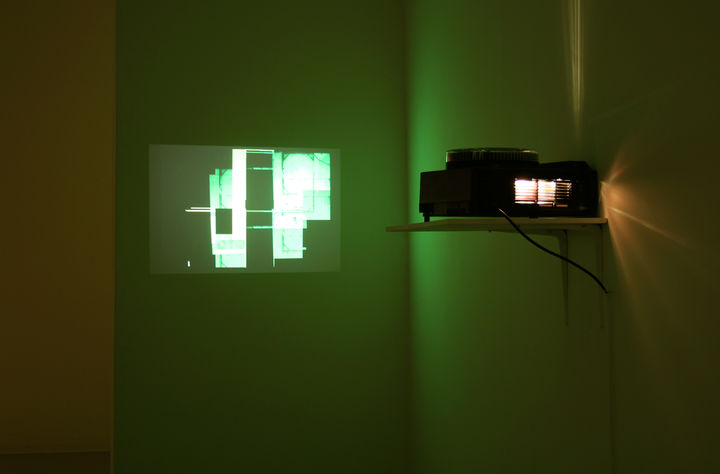

Four site and time-specific installations that took place 90 degrees apart on the equator (the meridian line of zero) and were photographed 6 hours apart to create a 24 hour earth cycle.

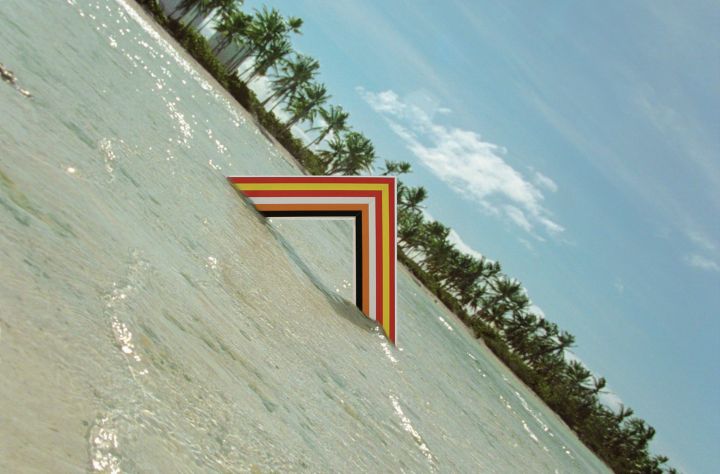

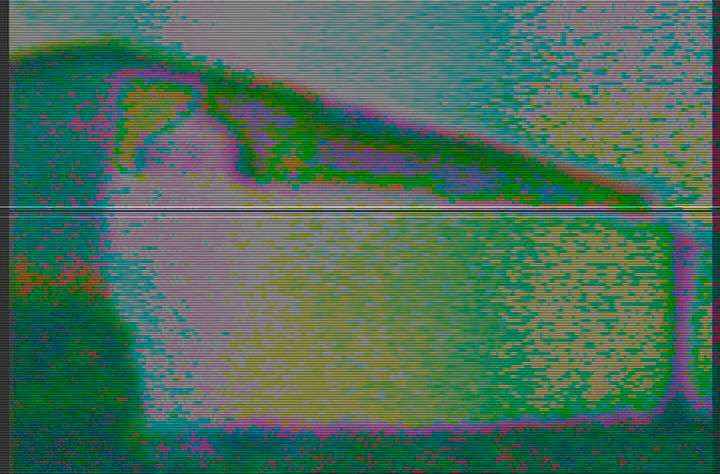

Sumatra 100° East, Kiribati Island, 170° East (4pm); Ecuador, 80° West (10pm); (10am); Gabon 10° East, (4am)

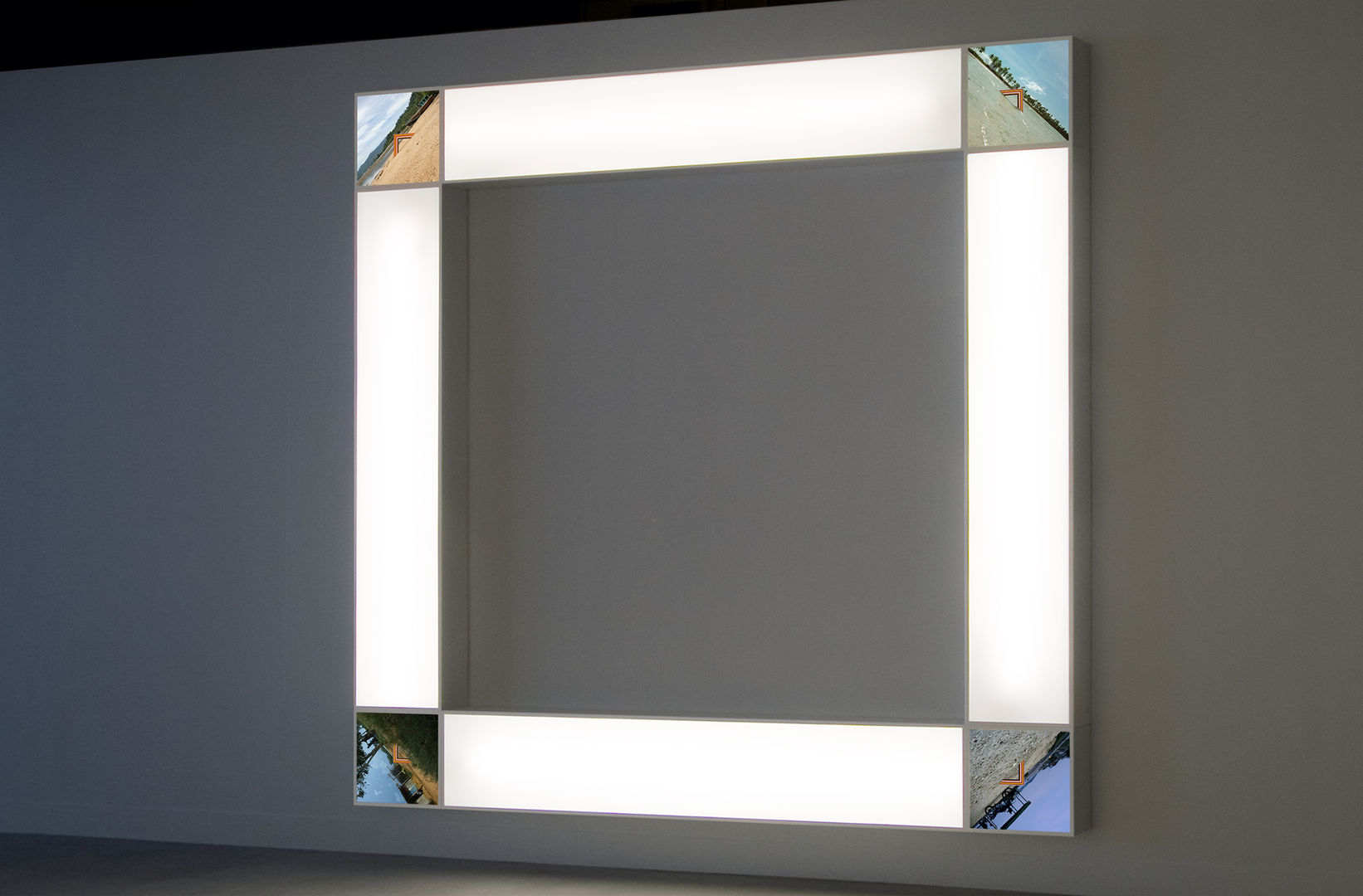

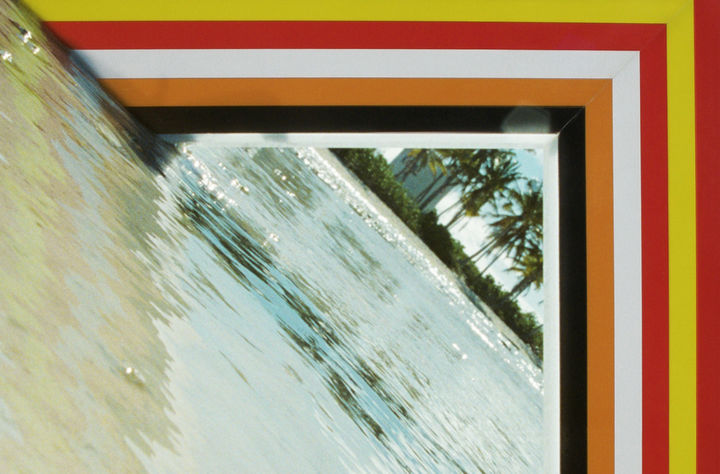

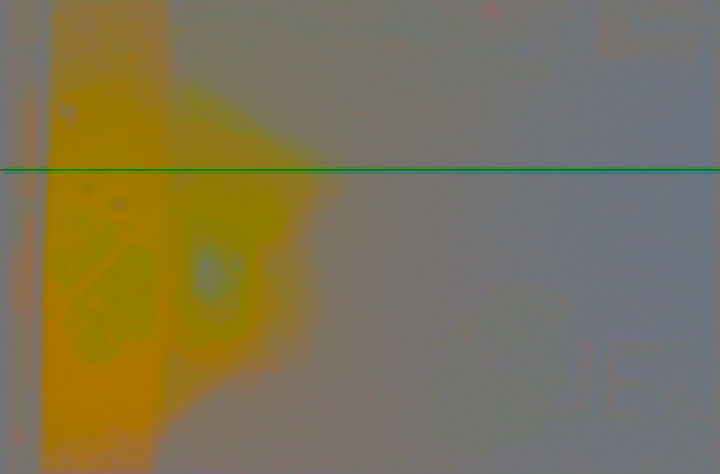

The portable sculpture was back lit with an embedded solar light unit, this set up a contrast between fluctuating exterior natural light and interior light moderated through technology to maintain consistency.

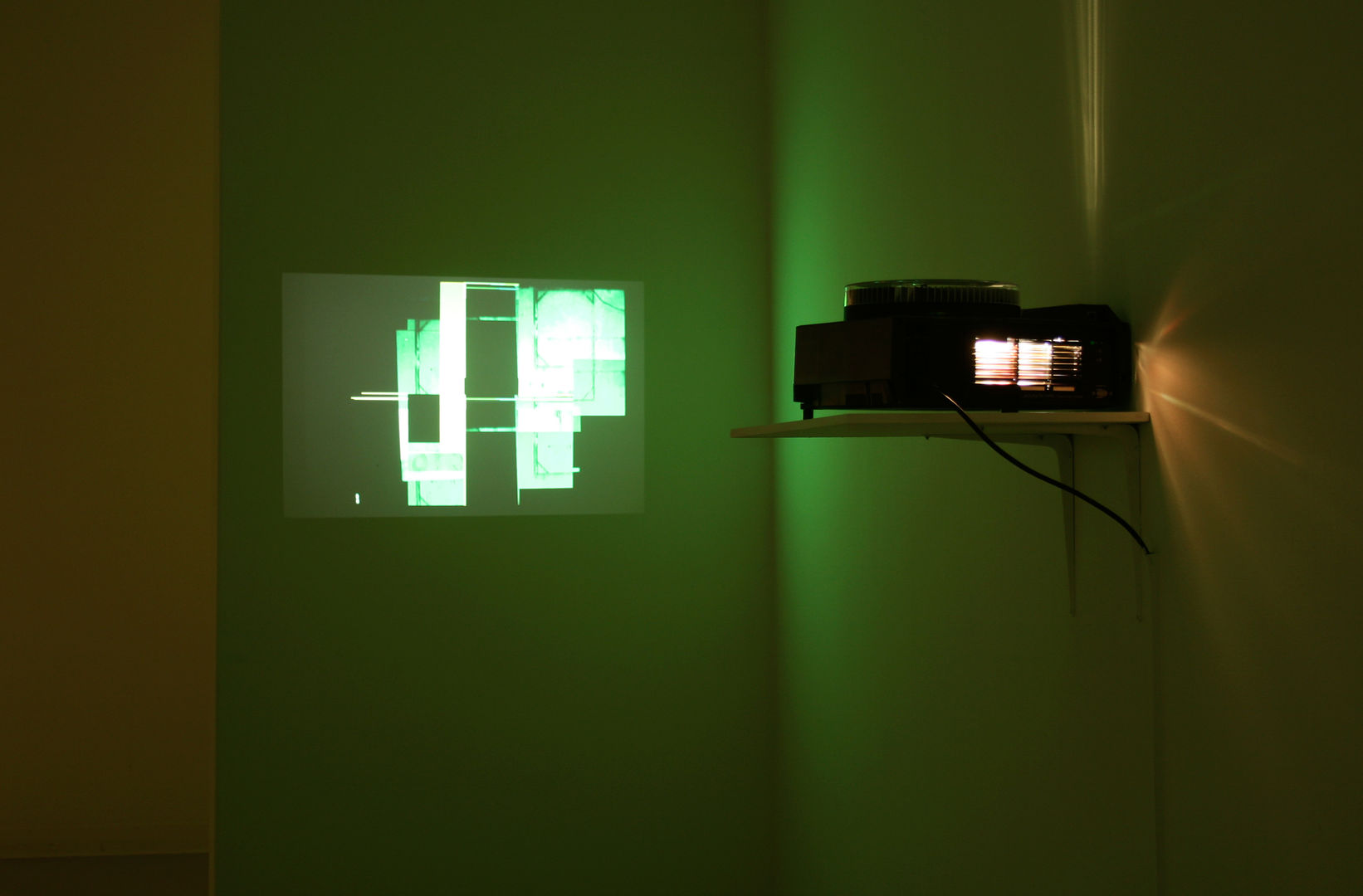

Duratran photographic prints with lightbox, 3.2m x 3.2m, 4-channel video, sound work, 2-chanel slide loop, artists book

Excerpt from - 90 Degrees Equatorial Project, by Russell Storer 2007, Head Curator International Art, National Gallery of Australia:

The phrase 'four corners of the globe’ is an obvious antilogy, yet it’s one we take for granted. It doesn’t specify anywhere in particular, merely indicating an all-encompassing spatiality. If we were, however, to try and locate these magical corners, where might they be found? The word 'corner' indicates something slightly shadowy or forgotten, a dusty, neglected pocket of a place, far from the comfortable centre of things.

It is when we are forced to consciously consider this process of perception that another form of experience is opened up to us. Art, Kravagna argues, has the potential to destabilise our connection to our surroundings and establish a new set of cognitive conditions and social relations. Through this 'suspension of certainty', there is the possibility for a shift in subjectivity. In his search for the world’s four corners, James Geurts offers us a different kind of frame, another mode of looking at (and for) other places, basing his method on aesthetic rather than cultural or economic grounds. Employing cartographical co-ordinates, light conditions and topography as formal systems, Geurts presents us with the bare minimum of information about 'place', structuring his work instead around a sculptural intervention at each site. Our preconceptions about these remote sites become disrupted by this surreal interloper; they become actively involved in an event, rather than being illustrations of the 'tropical', the 'peripheral', or 'the Third World'.

East Koto Padang in Sumatra, East Kango in Gabon, West Pedernales in Ecuador and East Kiritimati Atoll in the Pacific are linked only by the artist’s interest in creating a visual metaphor for our rationalising relationship to the world. Through an accident of geography, they are located at 90º angles from each other around the equator. On traveling to each site, Geurts searched for a suitable location in which to place his sculpture, an internally lit triangular form featuring bold stripes of red, yellow, white, orange and black. The sculpture’s minimalist aesthetic connects it to art-historical discussions of subject-object relations, although it exists here purely as something to be photographed, a performance for the camera to be reconstituted later. Its link to land art is obvious, and the artist has referenced Robert Smithson’s ideas on scale in discussing the work. 2) Smithson’s understanding of scale as determined by a conscious awareness of perception, of releasing it from the strictures of physical size into the realms of metaphor, aligns with Kravagna’s 'suspension of certainty', and allows Geurts’s little plastic boxes to literally frame the earth.

1) Christian Kravagna, 'Political arts, aesthetic politics, and a little story about the Nachträglichkeit of experience', in Things we don’t understand, exhibition catalogue, Generali Foundation, Vienna, 1999

2) p.95. James Geurts, interview, Photofile Issue 80

ARTLINK Magazine | The South Issue: New Horizons, Ian Hamilton- 90 Degrees Equatorial, Issue 27:2

RealTime Arts | Issue 79, Samara Mitchell Framing the World